Thursday, March 17, 2016

Martial: John Prine and Merle Haggard

Purchase: John Prine: Sam Stone

Purchase: Merle Haggard: A Soldier’s Last Letter

I’m taking a bit of creative liberty on our theme - martial - to talk about two songs concerning the military experience.

One song strikes me as poetic than musical, in the way it deals in stark imagery to show the aftermath of war and the kinds of wounds that don’t heal. The other is a bit of old-style country balladeering that unfortunately plays on cringe-inducing cliché and motif in a way that only country music can. A little on that idea before we get started. Sometimes, country music can be lazy—silly tropes repeated to the point that the simple use of an easily recognizable image stands blatantly for a resounding and universal symbol. Think about all the times you’ve heard the mention of American flags, mom, apple pie, Jesus and fast cars. I mean used seriously, without the requisite irony. A lot of country artists get away with lyrical murder, mining the same worn out themes and images – yet people fall for it, think formula makes for value. But, I guess people make John Grisham a bestseller, too, so when we look at music, sadly, quality is not the standout arbiter of quality.

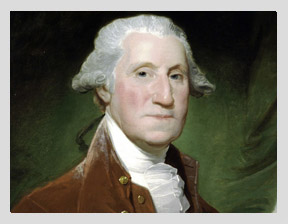

But, this is not the case with John Prine, the old-soul minstrel and bard of American music. From his withered voice, to his minor key arrangements, Prine reminds me of troubadour of old, singing to tell a story, using words and story with the musical accompaniment as an afterthought. Let’s say this: Prine’s influence as a songwriter is beyond measure. Does he need a great voice, when the hand of God moves his pen? Probably not.

Sam Stone is a song about a veteran returning from an overseas war who comes back to his family with “shattered nerves” and “shrapnel in his knee.” Our soldier, Sam Stone, with a “Purple Heart and a monkey on his back”, turns to drugs to ease his pain. What we have is a story, told through the bleak imagery of isolation, emptiness and the lingering odd sensation of how one sees the world when they are high. What is most striking is the underlying idea that even though the battlefield is nowhere near, our protagonist is still in dangerous proximity to death. In reality, Sam Stone left one war behind and came home to another one, and it is this war with his own demons that finally kills him and leaves his family broken and abandoned.

Prine has always been interesting to me: his voice can be grating. I imagine a lot of people who don’t know Prine would be inclined to turn him off, much like they would hearing Dylan’s distinctive delivery. But, lyrically, he is unrivaled. Reading Prine is like delving into a modern Whitman, sans the listing and cataloging. This is the writer of the everyman, vulnerable to the failings of the human heart, of age and distress, of societies’ brutish business and the dangers found lurking in the landscape of our everyday world. His melodies are lush, complicated and complex, building from a simple phrase and growing outward to gorgeously orchestrated compositions. Deceptively simple. Subtle. Beautiful. John Prine’s music works in ways that is rare – more than songs, carrying the emotional weight of a poem.

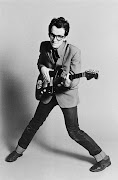

Now, let’s move on to the other song. I feel a little ashamed calling any song by the great Merle Haggard cheesy, but A Soldier’s Last Letter is a classic, but it’s also classic silliness. Penned in the epistolary form, A Soldier’s Last Letter is just that: a last letter written from the battlefield, from a soon to be dead soldier to his mother. The first two stanzas deal in the classic motifs of duty and remembrance, while the second half of the song details the mother’s reaction to the letter, reading it long after her darling boy, the one she used to yell at for coming home with mud on his shoes, has been killed. It’s a pretty song, I suppose, but what gets me is the way it ends: the mother, distraught at the loss of her son, goes down on her knees to pray. She prays the God will watch over all the other sons, but she also prays: “…dear God, keep America free.”

It strikes me as odd that a song like A Soldier’s Last Letter is considered a classic. It is classic only in playing on the same silly tropes so many patriotic songs use: mom, freedom… It starts off interestingly – but to think a mother, in the immediate wake of learning her son is gone, still finds it in her heart to pray to keep America free? It’s the kind of song that evokes lots of cheers and chanting – patriotism, especially in a country song, is a notion vulnerable to misuse and to childish sentiment. You think about performers that bandy about the stars and stripes as part of their image rather than the hard fought and contentious concept that democracy and freedom really is, and conception gets muddy. Merle Haggard speaks to freedom, hard living and independent, rugged individualism. That’s great. That probably is American. But then what about some 10-cent jackass like Toby Keith, and his knee jerk patriotism, or Eric Church (who I do like, but I think his metaphors are bargain basement cheap) and you can see a difference. Perhaps country music has to delve into those overused ideas—it could be an essential part of the genre, just like something jumping out of the shadows is key to horror films. I don’t know.

I reluctantly use The Hag as a bad example - a silly song in an otherwise pretty great catalog - of what is frustrating in country music. I listen to a lot of modern country, by virtue of Spotify (I get to listen, rather than buy, so it’s easier than ever to get a feel for what is trending). And, I’ve been really bothered by how shallow a lot of it is - and how bad songwriting is so easily considered “good.” Merle isn’t a bad songwriter, by any stretch, though I have always hated Okie from Muskogee, and the conservative, asinine divisiveness of that song and the point it tries to make in attacking one set of values in favor of another, equally oddball set. But, it’s an old song now, a relic of an era.

So much of today’s country music comes off as lazy—overused clichés meant evoke the most predictable response. I guess those easily recognized values are best to create mass appeal. But, when you look at great writers and how they don’t ever achieve the status that so many lousy ones do, it can be frustrating. And make for some bad music.

Posted by Andy La Raygun at 7:56 AM

Labels: John Prine, Martial, Merle Haggard, military

blog comments powered by Disqus